REVIEWS

OF RICKY LEE'S BOOKS

SI AMAPOLA SA 65 NA KABANATA

Lav Feorillo Petronilo A. Demeterio III, Ph.D.Diaz

Pamantasang De La Salle-Maynila

Ang pagpasiya ni Lee na magsulat ng mga nobela ay tila bahagi sa pag-ikot ng kaniyang landas bilang manunulat pabalik sa kaniyang pinagmumulang larangan, ang literatura.

...

Itinuturing ko ang nobelang Amapola bilang isang kontra-diskursong bakla at hangad kong maipakita at mahimay ang mga tiyak na estratehiyang ginamit ni Lee para hamunin at tibagin ang homopobikong kamalayan nating mga Pilipino. Kaya ang aking sanaysay na ito ay may dalawang pangunahing seksiyon na sumuri sa mga konteksto at inter-tekstong ginamit ni Lee para banayad na dumaloy ang kaniyang kontra-diskurso, at sa mga tiyak na estratehiyang nabanggit na. Mahalagang linawin sa puntong ito na ang katagang "baklang Manilenyo" na ginamit ko sa pamagat ng aking sanaysay ay tumutukoy sa kolektibo ng mga baklang residente ng Metro Manila, na may mga partikular na sitwasyon ng pagkakaapi at pinaghuhugutan ng lakas na maaaring naiiba sa mga baklang naninirahan sa ibang lokasyon ng bansa. Ngunit hindi ko isinara ang posibilidad na may makukuhang aral ang mga baklang intelektuwal mula sa ibang rehiyon galing sa aking pagsusuri na maaari nilang gamitin at patalasin pa para sa kani-kanilang mga kontradiskursibong proyekto...

Bliss Cua Lim

Author, Professor

"What captivates me about Amapola’s irreverent retelling of the Filipino origin legend of the first man and first woman is not only that it retrospectively reframes the established legend as a heterosexist narrative by rescripting it as the origin story of the first bakla. It is that “Legend of the Bakla” queers the very desire for origins through its casually flamboyant insistence on multitemporality. When Amapola describes Bathala, the Divine Creator as wearing a fabulous “bonggaderang headdress,” or characterizes the first unnamed queer creature as alternately mahinhin (feminine/ femme) or pa-mhin (masculine/ butch), the peppering of gay slang accomplishes a queer speaking of Bathala that reimagines swardspeak to be coeval with the origins of the world, anachronistically contemporaneous with the moment of Creation itself. The incongruously funny juxtaposition of the conventions of origin legends alongside swardspeak comes through with particular clarity in a spoken word performance of this very scene, recorded on digital video, at the novel’s book launch in November 2011.

At that star-studded, high profile book launch—a testament to Lee’s standing in the Filipino film industry as one of its most respected and prolific screenwriters— Jon Santos, a celebrity impersonator who came out publicly as married gay man in 2008, read an excerpt from the novel, “Legend of the Bakla” to a large and very receptive audience If one of the things a transmedial analysis pays attention to is the question of what “medium x [can] do that medium y cannot” (Ryan 35) and the ways in which remediation profoundly transforms precursor texts, then certainly the online video of Santos’ live spoken word performance vivifies, in ways the novel cannot, those queer codes of style, vocal delivery and bodily performance that are characteristic of swardspeak. Lee’s novel is written primarily in Filipino (the national language based largely on Tagalog in addition to other linguistic borrowings) and Taglish (a mixture of Tagalog and English), with swardspeak words and phrases sprinkled liberally throughout the text."

Caroline Sy Hau

Chinese-Filipino author, Professor

"While Lee's first novel, the bestselling Para Kay B (O Kung Paano Dinevastate ng Pag-ibig ang 4 out of 5 sa Atin), explored the intricate permutations of desire and intimacy in a series of interlinked stories, Si Amapola sa 65 na Kabanata paints a vivid portrait of its reluctant hero(ine) on a broader canvas in which past and present, public and private, politics and culture intersect.

Set in the Morato District in Quezon City, where rich and poor, officials and criminals meet and mingle, and home to the best bookstore in the country but also to restaurants and bars and massage parlors, the novel is fearless in marrying demotic speech--particularly swardspeak (gay lingo), with its hilarious, often ironic, mixing and appropriation of Philippine languages, English, Spanish, Japanese, and others--to ethical debate. Not since Jose Rizal's Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo has a comic novel probed so deeply the heart and viscera of politics and the imagination in the Philippines.

Si Amapola ranges widely across the Filipino landscape, offering a memorable cast of characters: indomitable, donut-chomping manananggal Sepa, taking (Andres) Bonifacio with her on a ride in the night sky; faithful Nanay Angie, who stood by her adopted child through all his/her personality and career changes; stalwart Emil, devoted fan of Superstar singer and actress Nora Aunor, surrounded by his extensive collection of memorabilia and dreaming of his idol's return from exile in America; vengeful Giselle, saddled with an abusive family and finding love in the arms of an Isaac who is present to her only intermittently and then gone forever; and self-righteous Trono, who becomes president on the basis of a campaign promise to "clean up" the country, but whose war against poverty and corruption also entails purging the country of "deviant" elements such as aswangs and homosexuals."

THE NOVEL PINOY NOVEL

Joel David (2011)

The results of the recently concluded American presidential elections seemed guaranteed to make everyone happy – except for the Republican Party and its now less-than-majority supporters. American conservatives could have spared themselves their historic loss if they had taken the trouble to inspect the goings-on in a country their nation had once claimed for itself, the Republic of the Philippines. The admittedly oversimplified lesson that Philippine cultural experience demonstrates is: when conservative values seek to overwhelm a population too dispossessed to have anything to lose, the pushback has the potential to reach radical proportions.

This is my way of assuring myself that a serendipitous sample, Ricky Lee’s recent novel Si Amapola sa 65 na Kabanata (Amapola in 65 Chapters), could only have emerged in a culture that had undergone Old-World colonization followed by successful American experimentations with colonial and neocolonial arrangements, enhanced by the installation of a banana republic-style dictatorship followed by a middle-force uprising, leaving the country utterly vulnerable to the dictates of globalization and unable to recover except by means of exporting its own labor force – which, as it turns out, proved to be an unexpectedly successful way of restoring some developmental sanguinity, some stable growth achieved via the continual trauma of yielding its best and brightest to foreign masters.

Si Amapola is one of those rare works that will fulfill anyone who takes the effort to learn the language in which it is written. A serviceable translation might emerge sooner or later, but the novel’s impressive achievement in commingling a wide variety of so-called Filipino – from formal (Spanish-inflected) Tagalog to urban street slang to class-conscious (and occasionally hilariously broken) Taglish to fast-mutating gay lingo – will more than just provide a sampling of available linguistic options; it will convince the patriotically inclined that the national language in itself is at last capable of staking its claim as a major global literary medium. In practical terms, the message here is: if you know enough of the language to read casually, or enjoy reading aloud with friends or family – run out and get a copy of the book for the holidays. The novels of Lee, only two of them so far, have revived intensive, even obsessive reading in the Philippines, selling in the tens of thousands (in a country where sales of a few hundreds would mark a title as a bestseller), with people claiming to have read them several times over and classrooms and offices spontaneously breaking into unplanned discussions of his fictions; lives get transformed as people assimilate his characters’ personalities, and Lee himself stated that a few couples have claimed to him that their acquaintance started with a mutual admiration of his work.

This is the type of response that, in the recent past, only movies could generate – and the connection may well have been preordained, since Lee had previously made his mark on the popular imagination as the country’s premier screenwriter. The difference between the written word and the filmed script, per Lee, is in the nature of the reader’s participation: film buffs (usually as fans of specific performers) would strive to approximate the costume, performance, and delivery of their preferred characters, while readers would assimilate a novel’s characters, interpreting them in new (literally novel) ways, sometimes providing background and future developments, and even shifting from one personage to another.

Si Amapola affords entire worlds for its readers to inhabit, functioning as the culmination of its author’s attempts to break every perceived boundary in art (and consequently in society) in its pursuit of truth and terror, pain and pleasure. For Lee, the process began with his last few major film scripts (notably for Lino Brocka’s multi-generic Gumapang Ka sa Lusak [Dirty Affair]; 1990) and first emerged in print with his comeback novellette “Kabilang sa mga Nawawala” (Among the Missing; 1988). More than his previous novel Para Kay B (O Kung Paano Dinevastate ng Pag-ibig ang 4 Out of 5 sa Atin) (For B [Or How Love Devastated 4 Out of 5 of Us]; 2008), Si Amapola is a direct descendant of “Kabilang,” at that point the language’s definitive magic-realist narrative.

Despite this stylistic connection Si Amapola is sui generis, impossible to track because of its fantastically extreme dimensions that abhor any notion of middle ground. The contradictions begin with the title character, a queer cross-dressing performer who possesses two “alters”: Isaac, a macho man (complete with an understandably infatuated girlfriend), and Zaldy, a closeted yuppie. His mother, Nanay Angie, took him home after she found him separated from his baby sister and, notwithstanding the absence of blood relations and any familial connections, raised him (and his other personalities) with more love and acceptance than most children are able to receive from their own “normal” relatives. A policeman named Emil, a fan of real-life Philippine superstar Nora Aunor, then introduces Amapola to his Lola Sepa, a woman who had fallen in love with Andres Bonifacio, the true (also real-life) but tragically betrayed hero of the 19th-century revolution against Spanish colonization. Lola Sepa moved through time, using a then-recent technology – the flush toilet – as her portal, surviving temporal and septic transitions simply because she, like her great-grandchild Amapola, happens to be a manananggal, a self-segmenting viscera-sucking mythological creature.

Already these details suggest issues of personal identity and revolutionary history, high drama and low humor, cinematic immediacy and philosophical discourse, and a melange of popular genres that do not even bother to acknowledge their supposed mutual incompatibilities; if you can imagine, for example, that a pair of manananggal lovers could be so abject and lustful as to engage in monstrous mid-air intercourse, you can expect that Lee will take you there. The novel’s interlacing with contemporary Philippine politics provides a ludic challenge for those familiar with recent events; those who would rather settle for a rollicking grand time, willing to be fascinated, repulsed, amused, and emotionally walloped by an unmitigated passion for language, country, and the least and therefore the greatest among us, will be rewarded by flesh-and-blood (riven or otherwise) characters enacting a social drama too fantastic to be true, yet ultimately too true to be disavowed.

At the end of the wondrously self-contained narrative, you might be able to look up some related literature on the novel and read about Lee announcing a sequel. Pressed about this too-insistent meta-contradiction of how something that had already ended could manage to persist in an unendurable (because unpredictable) future time, he replied: “Amapola the character exists in two parts. Why then can’t he have two lives?” Nevertheless my advice remains, this time as a warning: get the present book and do not wait for a two-in-one consumption. The pleasure, and the pain, might prove too much to bear by then.

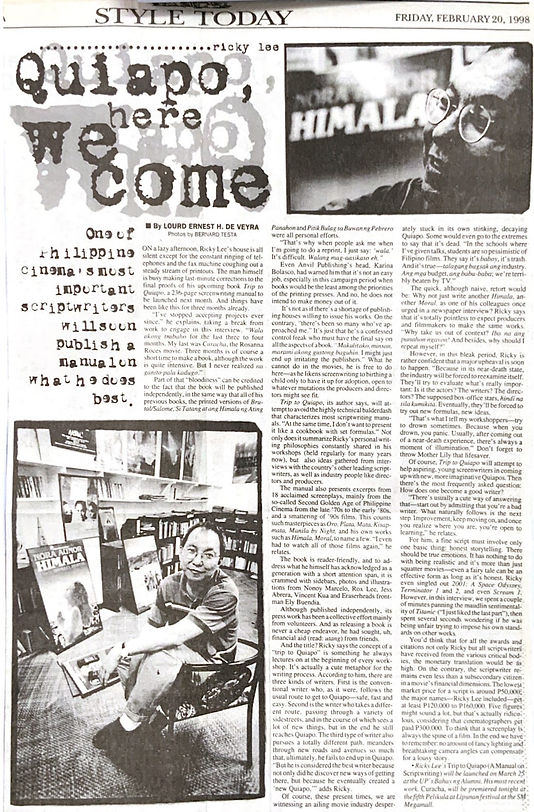

TRIP TO QUIAPO

PARA KAY B

Blurbs/Reviews

Ricky Lee is one of the best storytellers of this generation. Formidable and vulnerable at the same time. His fiction is truthful. Para Kay B is hilarious, painfully real, infinitely fascinating, riveting and is crafted deftly by a master. The characters are totally insane, just like you, me and Love.

BOY ABUNDA

Media Personality

Ricky Lee is one of the best Filipino writers ever, bar none. This long overdue novel will prove that he rules on the page as well as on the screen.

ELY BUENDIA

Musician

Na-enjoy ko ang nobela, sobra. Isang upuan lang sana sa akin ito, kaya lang ginagawa ko pa ang Dyesebel kaya inabot ako ng dalawa. Napaka-witty at sensual kasi magsulat ni Ricky. Ang sarap ng bagsak ng mga salita. At saka wala siyang pakialam sa rules o conventions. Basta kukuwentuhan ka niya, at kesehodang nagdidirek ka pa ng sirena, wala kang choice kundi makinig at ma-in love. At one point nakalimutan kong nagbabasa ako ng nobela. Buong-buo ang mga character---nakikita ko na pati ang itsura nila, ang suot nila, pati mga location alam ko na. Parang nanonood ako ng movie na wish ko, ako sana ang gumawa.

JOYCE BERNAL

Film Director

Weeks after reading the novel, Ricky Lee’s characters continue to haunt me. They mesmerize, seduce, and provoke. There is hardly anything orthodox about them or the style in which their stories were written, but they are all so compelling because at the core of Ricky’s work is the universal, irresistible yearning to find love---no matter how flawed, painful, or even dangerous---as long as it makes us hope that it’s worth it. And it is. I wish I could film this novel, but not before I relish re-reading it again and again for its literary wizardry!

MARILOU DIAZ-ABAYA

Filmmaker and Educator

Namumukod ang mga akda ni Ricky Lee sa lalim ng pagdalumat at mapangahas na teknik. Nangunguna rin siya sa masikap na paglalapat ng teoryang pampolitika sa kanyang mga isinusulat.

BIENVENIDO LUMBERA

National Artist for Literature

Ricky Lee, perhaps one of the best-known scriptwriters in the Philippines of the last four decades, is also an important fictionist whose Palanca award-winning stories anticipated the postmodern narrative in Philippine fiction, where boundaries between genre (fiction and reportage) and realities (imagined and lived) are often blurred, if not totally wrecked. His involvement with Sigwa in the seventies also positioned him as one of the more committed writers of his generation. To say that the arrival of his first novel last year was long overdue is an understatement. Good thing, Para Kay B (o kung paano dinevastate ng pag-ibig ang 4 out of 5 sa atin) proved worth the wait: It exhibits Lee’s mastery of contemporary language, mindless of how the academicians would react, and showcases his skill in creating memorable individuals, breathing ordinary yet defamiliarizing lives. At first, we might be deceived that we were given stereotypical characters and worn-out scenarios, but a little later we would feel comfortable that Lee knew what he was doing and that they were all part of the book’s major scheme.

The novel was initially a story of five women whose experiences of love crushed them differently, save for one, as the title suggests: Irene, who had a photographic memory, could not forget the promise of love she was given when she was very young, only to find out years later that she was not even remembered by the man in her past; Sandra, who fell in reciprocated love with her own brother, only to cause his lifelong suffering in the end; Erica, who came from a community called Maldiaga where love was unheard of, left home wanting a taste of love, only to realize that she was not really capable of loving someone; Ester, a widow raising a sexually active gay son, finally admitted to herself that it was her female house helper and friend whom she really loved all her life; and finally, Bessie, the promiscous lover who seduced Lucas, who was incidentally the writer of all these five tales. The end of their stories opened the metafictional designs of the novel that were explored in the concluding chapter, where the Writer was presented as taking part in his own narrative, with conflicting visions of his own characters, both as people who supossedly lived real lives and as merely imagined personae. In the narrative rampage as the book reached its climax, the characters were able to confront the Writer, were able to decide amongst themselves for better endings in their respective stories, and were able to plea for salvation, and, well, yes, love, even in its most deceitful guise.

In a few concluding words to the book, Lee admitted that despite his success in writing film scripts, all he really wanted to do in life was to write novels. He also shared that he was able to write three novels in the last three years, and we were given a taste of the second one, called “Aswang,” which promises to be more hilarious, given the three-page excerpt. Perhaps Lee’s experiences and exposures with more popular texts, being also a creative consultant to many TV shows, paradoxically invigorates his sensibility to come up with something this creative. Or probably he was really just born to write novels this refreshing that I can’t wait for what he has to offer next.

EDGAR CALABIA SAMAR

Writer-Educator

The Many Faces of Love (2009)

Danton Remoto's Review of Para kay B

Para kay B is the first novel of scriptwriter par excellence Ricky Lee, published by the Writers’ Studio and launched in a grand bash last December. Subtitled “O kung paano dinevastate ng pag-ibig ang 4 out of 5 sa atin,” the novel deals with love and its wreckages. True to form, Lee conveys his insights in a manner that shatters the usual realistic narrative mode of Philippine literature in Filipino. For in the end, he lets the author of the novel within the novel question not just the nature of love, but the nature of narrative itself. Who, in the end, gives meaning to a story? It also mirrors the novel’s central point: who, in the end, benefits from love? And if love is so melodramatic and so sad, why do we even need it?

The answer is similar to what mountain-climbers say: we climb the mountain because it is there. We fall in love, or other people fall in love with us, because the feeling is here inside us; or there, inside the other person. Or, as what happens to some characters in the novel, it is elsewhere, neither here nor there, not for one man or for one woman, but in the ambiguities that seem to characterize love itself...

BAHAY NI MARTA

Ricky Lee's Ang Bahay ni Marta and My Poem An Old House from Specks Anthology

September 29, 2020

Melodramatic with tempered magical realism, Ang bahay ni Marta is a nice read and not that demanding for one's time because it is just a small thin book. As at any other times, Ricky Lee emphasizes the obligation of a writer/storyteller/everyone to tell the story so we won't forget.

And it is not just a storytelling of an anecdote but of one's history. Given the background of Ricky Lee as an activist imprisoned during the Marshal law where he went to the point of committing suicide, I believe it is our obligation to not forget how we fought for democracy, we should not forget the times it was violated. The tangible house of Marta may be dismantled but once the story is told, it is still intact in our consciousness and we will never never forget what happened inside the house, to our nation...

BAHAY NI MARTA REVIEW

from Foot and Fire

BOOK REVIEW: Bahay ni Marta by Ricky Lee

June 22, 2018

Lee does not dictate nor preach lessons to his readers. He throws rhetorical questions that leave a blank space for the reader to fill in themselves. He jests the reader to question their own understanding of good and evil; faith and fanaticism; and what is redeemable and not. I carefully nodded as he tackled the lives of religious leaders in which they are individuals who sin despite their decrees. In that, Lee proves to be brave and unrelenting...

Dexterous_Totalus

KUNG ALAM N'YO LANG

BOOK REVIEW: Kung Alam N’yo Lang by Ricky Lee

July 8, 2017

Kung Alam N’yo Lang is a bind up of four short fiction stories (each almost a “dagli” or flash fiction) about children but are not intended for children. It is seemingly a children’s book parents would read at night before they are tucked in bed but really, this is a Pandora’s box of monsters we fear when the lights are off.

The very words of Lee that captured my attention:

“May mga bata sa loob nating matatanda. At kapag tiningnan mo namang mabuti ang mga bata, minsan ay makikita mo kung magiging ano sila sa kanilang pagtanda.”

That we see a child when we look into a man’s eye and in the same boat, we gaze into a child’s future when you wallow deep into their carefree little eyes. This piece of work scrutinizes the humanity in everyone – an innocent question leading to darker alleys and nooks. It tells stories about these kids and and how there musings reflect the adult dilemmas of faith, mental illness, politics, corruption, grief and greed. If they only knew…